published in Film Criticism Journal, Winter 2019

After the recent passing of “the grandmother of the Nouvelle Vague,” newspaper articles reflected back on the work of filmmaker Agnes Varda. Her debut film, Cleo from 5 to 7 continues to fascinates. As we watch a young woman struggling with her demons, set against a beautiful backdrop of 1960s Paris, Varda’s masterpiece ticks all the boxes of the Nouvelle Vague aesthetic. The film cleverly fuses mysticism, everyday life and tragedy without losing its lighthearted French flair. The film is also deeply personal, empathetic and (self-) reflexive.

Cleo from 5 to 7 tells the story of a young female singer who changes her self-perception in the course of a fateful afternoon. As Cleo fearfully awaits the results of a biopsy, she embarks on a journey of self-discovery. Tired of being reduced to her charm and beauty, Cleo makes a significant transition. The film is full of mirrors, figuratively and symbolically; it revolves around Cleo’s reflection, how others perceive her, and images of fate which swirl around her.

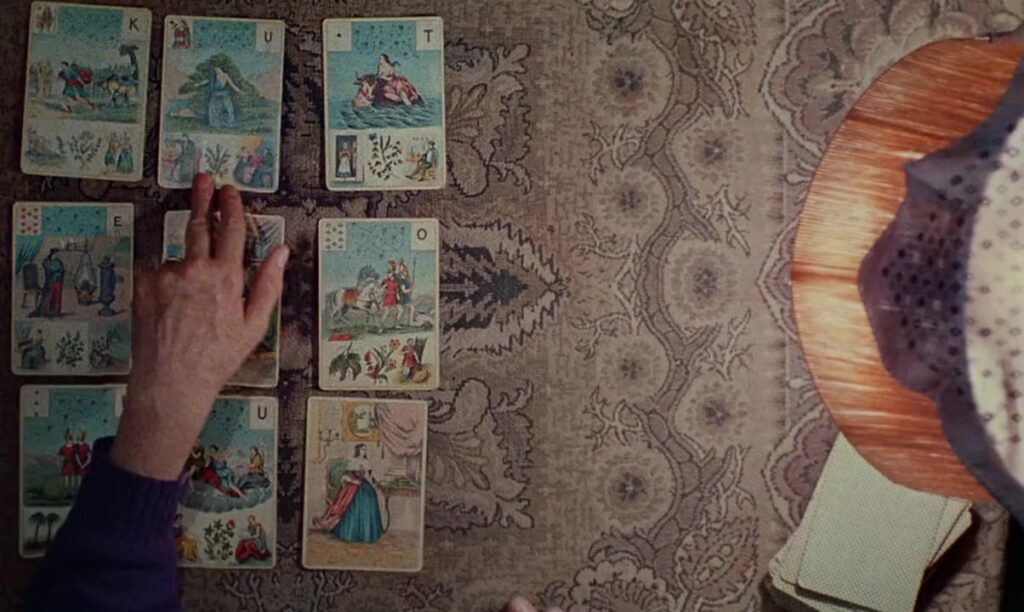

The film’s mirror motif can be divided into three analytical parts. In his famous psychoanalytic formulation, “the mirror stage,” Jacques Lacan states that what we think of our own identity is actually pure Imaginary, a construct behind which the real subject resides.[1] Cleo from 5 to 7 starts with a tarot card reading which predicts death. Cleo immediately tries to reassure herself by looking into a mirror.

Cleo has a constructed image of herself, and easily finds comfort in it. Her beauty is her proof that she is more alive than the others around her. The mirror’s reflection validates her existence. Walking down the streets of Paris, Cleo is objectified by both men and women. At home, she finds herself surrounded by her maid and friends, who produce her music. However, she is not able to write any songs on her own.

A song that sounds like an eulogy to herself triggers an emotional reaction. A different consciousness suddenly evolves. She leaves her home and enters a second stage of mirroring. Continuing her journey in the streets, she now blends with the crowd, no longer the one being looked at. No one pays attention to her; she is anonymous behind her glasses.

This new role culminates when Cleo meets a friend, a nude model for sculptors. She gazes in amazement at her friend’s skillful poses. Cleo’s new role as viewer has reached its pinnacle. In this section, Cleo’s image is only reflected back at herself through broken glass. When Cleo looks in a mirror in a cafe, it reveals a fragmented, distorted perception of herself.

In Lacanian terms, Cleo does not perceive herself as a whole anymore; she becomes detached from her previous life. For Lacan, the moment in which the infant looks at his reflection in the mirror is when the child develops a sense of self. Before this, the child doesn’t think of himself as an individual at all, but simply exists as a unified subject, as one with his surroundings. Therefore, the development of a sense of identity leads to a distorted image of one’s true self. Lacan insists that we are detached, oblivious to our real selves. This new relationship the child develops between the subject and object expresses the tension between the Imaginary and the Real. Cleo is now faced with a crisis. She recognizes distortion, becoming an adult with nothing to lose. Her real self can now emerge.

The third and last stage of Cleo’s journey comes via her encounter with the soldier, Antoine. His gaze at her is unspoiled, marked by innocence and kindness. He sees her as a whole being. For the first time, we see that Cleo is not just a spoilt child, but a woman knowledgeable about the arts. Suddenly, she is a confident, intelligent woman. One sincere look at her has accomplished the transformation.

There are no mirrors or reflections of any kind during the encounter with Antoine. When Cleo sings and dances in the park, she does it for herself; there are no viewers. Antoine calls her by her real name, Florence. In response, Cleo displays the demeanor of someone who is truly at peace with herself. The framing and camera angles suggest equality between the two human beings. Cleo is finally accepted for being her true self. Cleo completes the journey from fragmented ego images constructed by reflections to a whole being, one who can exist without mirrors.

Varda’s masterpiece takes us on a complex journey of possession, loss, and the finding of stable identity. Released in 1962, the film was part of a general movement toward female empowerment that spanned across Europe and Hollywood. However, the film is more than just a celebration of a young independent woman. Varda not only shows us where belittlement and oppression come from, she also presents a defense against them. She fights female objectification and loss of self with the mise-en-scene device of the mirror.

In an image-based society where one’s identity has come to be dominated by selfies, and defined by what other people see on social media, we are subject to identity fragmentation. The identity of the self has become marketable in a world where an “influencer” is a job and not merely a rhetorical function. To add insult to injury, success in such a world is ironically attributed to “authenticity.” Needless to say that Cleo’s journey is just as relevant today as it was in the 1960s.